I have never been a fan of online family trees. Whilst absolutely respecting other people’s right to make whatever choice suits them, it was something that I always vowed, quite vehemently, I would never do. I was wrong. First of all, a word about why I chose to keep my family tree offline. When I started my research, over forty years ago, there was no online. I suspect if I were a new recruit to genealogy now I would make some different choices. When I got fed up with hand-drawing copies of family trees to share with others, I capitalised on the fact that I had a computer and purchased some genealogy software; Family Tree Maker. I can’t remember exactly when this was but it was on floppy disks and I think it was version 3. I still use Family Tree Maker. The trees it produces are not ideal but it suits me better than the alternatives. The fact that my handwriting is an exercise in advanced paleography played no small part in my decision to abandon hand-drawn trees.

Let me be clear, my reluctance to put a family tree online had nothing to do with me not being willing to share my information; I have been doing that since 1977. The surnames that I am interested in have been widely advertised for decades and are listed on this website. Over the years, many distant relatives have benefited from my research and vice versa. Purely because of the length of time I have been researching, I often have more to give than receive but that is fine. I love to share information but I do like it to be a two-way process. I want it to be accompanied by a conversation about the sources I have used and why have I made the connections that I have, or why I have not. I want to share the stories and the contextual detail that I have researched, not just the names and dates. To this end, some narrative accounts about my ancestors are now also available on my website.

This has worked well for me until very recently. Why would I change? I have been vocal about my opinion of many of the genealogies that you find online. Let’s just say I am not impressed by vast, unsourced, ‘grab it all’ trees containing biologically impossible data and scores of unverifiable connections. I do accept that there are well-researched, accurate pedigrees, compiled by proficient genealogists on the www but there is also an overwhelming amount of dross. So much so that extracting the gems has made looking for the proverbial needle in a haystack seem like child’s play.

People have often marvelled that I can do family history research without an Ancestry account, particularly as I do still do some professional research. I have never felt the need. I have subscribed to FindmyPast since before it was called FindmyPast and that suits me because the coverage is better for the counties that I need most often. When I began researching in the years B.C. (before computers), tracing your family history was impossible without going to archives and this is still key to the work I do. In fact, I believe that archival research is still essential for all researchers, as so much is not online.

A few months ago, having had my DNA tested with other companies, I decided that I might as well add Ancestry DNA to my collection of autosomal results. Before I parted with my hard cash, I considered whether having no Ancestry subscription and no online tree would make the test worthless. I realised that it would hamper my chance of encouraging contacts but I decided that it would still be useful, especially at sale price. The results arrived. I was offered a significantly reduced rate for an Ancestry subscription. So, tempted by the data sets, notably the London parish registers and PCC wills, I took out my first ever Ancestry subscription. I still had no intention of ever putting my tree online. I filled in my profile with my ancestral surnames but I resisted the exhortations to start my tree, even one that was private.

I had fun with my DNA matches, as expected, none of them close. I have two 3rd-5th cousins and 284 at 4th-6th cousin level, which I would guess is probably significantly fewer than most people. Some I had made contact with before. I could, I thought, just sit back, with my lack of tree and see if anyone contacted me. I worked out how some of the matches were connected to me using their public trees. I began to colour code them into groups. I was having fun. Everyone was banging on about ThruLines, that sounded fun too but of course I couldn’t connect to anyone with no tree. As I worked through my matches, I realised that I was prioritising those with public trees, of course I was, no real surprise. I contacted a few people, some replied, some didn’t, not unexpected. I found a third cousin in Australia, practically my closest living blood relative. Obviously, I reasoned, people are going to do the same as I did, start with those with public trees, then perhaps consider contacting a few with private trees if the common matches looked promising. With tens of thousands of matches, no one was ever going to get round to contacting poor little treeless me.

I umm and erred a bit and I took the plunge. My original intention was just to add my direct ancestors, not least because of the time it would take to add the results of forty years’ worth of research. The reasoning behind creating this tree meant that there was no point in making it private. My concession to privacy is that I have listed my parents as alive when they aren’t, so they can’t be seen and I would not consider adding my descendants. I still have numerous Cornish direct ancestors to add, some of those were acquired so long ago that they haven’t even made it to Family Tree Maker! I have filled in some siblings, particularly where it clarifies a DNA link and I will gradually add more.

Before I began, I worried if anyone would take an unsourced tree seriously (I wouldn’t) and I couldn’t face the thought of adding a trillion source citations, which I keep on a card index, yes, really, I do know it is 2019. Once I had begun, I realised that Ancestry make it quite easy to add sources, which was a relief. Their hints do contain some serious flights of fancy but these can be ignored. Of course, the sources that are attached to my Ancestry tree are a fraction of those that I have for some of these individuals but at least the tree is not unsourced.

Transferring a Gedcom wasn’t an option as I have multiple files. I could have created a composite tree by merging them but I thought it was quicker to start again. Everyone I have added has been verified using original sources, or images of those sources. I do not rely on indexes, although they are obviously a helpful gateway to the documents. For this reason, I have not and will not, graft someone else’s tree on to my own. Although I am equally committed to researching them, I have made no attempt to add my children’s ancestors, as the point of this is to understand DNA matches and these are not relevant to that task.

Admitting you are wrong is difficult but I like to think that I am open to altering my opinions and alter them I have. I now have a tree on Ancestry, I am even quite proud of it. It will never be the primary method of keeping my information. There are several reasons for this not least because I want to be able to work on my tree when I am not online but I have ‘come round’ to a certain extent and who knows, maybe my opinion will change again.

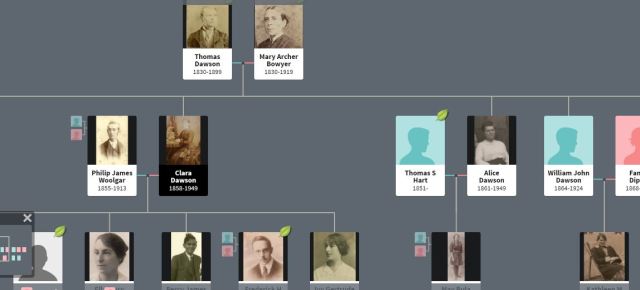

Part of a tree created at Ancestry.co.uk